In the Interests of National Security?

A very interesting article came to light over the weekend. Aftenposten.no (Norway’s Evening News – their largest newspaper) runs a story on GSM and A5/1, the encryption standard within GSM, reporting how the British requested weaker encryption.

A very interesting article came to light over the weekend. Aftenposten.no (Norway’s Evening News – their largest newspaper) runs a story on GSM and A5/1, the encryption standard within GSM, reporting how the British requested weaker encryption.

We have the Washington Post reporting that the NSA can break one of the encryption standards used to prevent eavesdropping on mobile calls. We will see that this is just the start – today any script kiddie with a few $ and a laptop can eavesdrop GSM.

We may all be 3G and 4G now, but very often voice and SMS is sent over the old 2G networks to preserve available bandwidth on the newer networks.

Now we apparently have the back-story that lead to this! Coincidentally I put up a short summary of GSM’s history only last week.

Way back in 1982 the GSM spec was being built. It took until 1990 to finally get to a complete set of specs. Aftenposten report that the original encryption standard proposed for use in GSM, A5/1, was deliberately and significantly weakened at the behest of the British (although a second source in these allegations simply reports it as ‘political pressure’).

The encryption standard originally proposed called for a key length of 128 bits. Jan Arild Audestad states that the British weren’t interested in strong encryption and actually protested against the security level that was proposed.

At the time the spec was being built this was exceptionally good. Even today 128 bit keys are considered out of reach for conventional brute force attacks.

By Audestad’s account, the British wanted a surprisingly weak 48 bit key. (DES from 1977 compromised on 56 bit as “adequate” (at the request of the NSA!), yet even that was suspected to be weakened as IBM had recommended 64bit keys) West Germany protested as they wanted strong GSM encryption to guard against spying by East Germany.

Another source, Peter van der Arend from the Netherlands reports that “The British argued that the key length had to be reduced. Among other things they wanted to make sure that a specified Asian country should not have the opportunity to escape surveillance”.

“The length was increased by the British – two bits at the time. They did not want to go further than 54 bits. And even though I argued against it, I eventually lost support from the others. And from that moment we had weaker security, and I am still angry about this”.

Ironically although the standard is claimed to be 64bit, the last 10 bits are always zero so the actual strength is 54bits.

Thomas Haug, who chaired the steering committee of experts that standardized the GSM system, adds “I was told by a British delegate that the British secret services wanted to weaken the security so they could eavesdrop more easily”.

The other thing we learn was introduced to the GSM spec, via political pressure, was the ability to turn off encryption without the mobile phone user knowing. (my emphasis)

But It’s Broken in Other Ways

As it turned out, mistakes (or politically pressured weaknesses?) in the GSM design mean that it’s relatively easy to break the encryption at the protocol level by exploiting a downgrade from A5/1 or the more current 3G A5/3 (KASUMI) to A5/2 which can be broken in seconds. Once the keys are obtained the handset can be allowed to upgrade again as astonishingly the encryption keys are the same between all three strengths of encryption.

As it turned out, mistakes (or politically pressured weaknesses?) in the GSM design mean that it’s relatively easy to break the encryption at the protocol level by exploiting a downgrade from A5/1 or the more current 3G A5/3 (KASUMI) to A5/2 which can be broken in seconds. Once the keys are obtained the handset can be allowed to upgrade again as astonishingly the encryption keys are the same between all three strengths of encryption.

So from a practical point of view it’s perhaps just delayed the free cracking of GSM as there were significant other issues. We have no idea if changes and tweaks were suggested to the protocols also. Of course, ignoring fun conspiracy theories, we can clearly see that the cause of this other attack vector is the deliberately weakened export encryption. Net result: Weaker encryption and a vulnerability for all.

We simply know that today any idiot with a few bottom of the range handsets and a laptop can eavesdrop a GSM call.

So What?

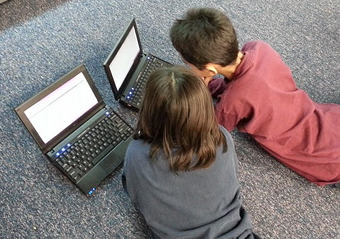

Today this is about the age you’d expect people to have enough tech knowledge to snoop anyone’s phone calls.

In other words it’s really easy!

If GCHQ / British Government managed to get the encryption weakened so that the security services can happily eavesdrop all targets “more easily”, then everyone can eavesdrop “more easily”. Everyone including the old East Germany, Soviets, Chinese, and any other nation that gets to be the current fashionable bogey man.

So in their world view it’s better that everyone is given security that’s a placebo. We end up with less (or no) security for all.

I can actually recall that one of the touted benefits, which was heavily publicised at the time, when GSM was rolling out was the secure encryption and the fact it was impossible for anyone to listen in. They made a point of explaining how much better that would be than analogue mobiles that anyone could listen in to. I guess it’s too late to complain to Advertising Standards.

There seem to be only two possible conclusions:

Either there is some fantasy world in which only they (the NSA or GCHQ) will be able to work around the weakened encryption. Clearly that’s not credible as the USA and UK don’t get a monopoly on good brains. Global education league tables seem to show that most clearly!

If by some miracle you actually subscribe to this view then roll forward ten years and encryption weak enough to be broken by only the NSA is now almost certainly within the capability of the French, Chinese, (very long list) etc. Is that still OK with you? What about the actual reality of today where any thief or kid with a couple of £15 handsets, a laptop and your mobile number can now eavesdrop you?

Or perhaps the “security” agencies simply don’t care that there is no security. Presumably those in the know get to use carefully restricted apps containing known strong encryption.

Neither option exactly fills you with confidence that they have the security “best interests” of their nation at heart. In fact they seem to simply not care so long as they can get their hands on more juicy data. Insecurity Services seems more apposite.

The simple binary choice is security for all, or vulnerable for all.

Which is really in the better interests of our nations and people?